| The Female Pelvis:

Some Anatomical and Symbolical Aspects Excerpts from "Os Órgãos Sexuais Femininos" Nelson Soucasaux |

|

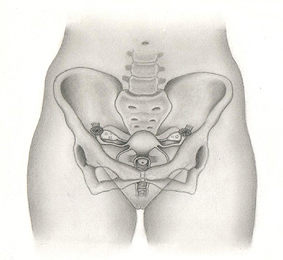

The ways women experience their genitals and the pelvis that houses them constitute a very special aspect of the mind-body relationship in the female sex. They consist of several anatomical, physiological, pathological, symbolical and archetypal experiences that have an enormous importance mostly in Psychosomatic Gynecology. The extremely rich symbolism that surrounds the woman's genitals, pelvis and belly contributes a lot for the correct understanding of the female psycho-physical constitution.

If we pay enough attention we will see that, from the symbolical and archetypal standpoints, the anatomical configuration of the vulva, vagina, uterus, Fallopian tubes, ovaries and the whole female pelvis exhibits very peculiar aspects. In a way, the female genitals and the woman's pelvic frame are deeply inter-connected, giving rise to an inseparable wholeness. Even considering that most of the female genitals are intrapelvic, the very typical configuration of the woman's pelvis just by itself lets us know its content.

It is pertinent to remember here that the very special anatomic features of the female pelvic bones are partly responsible for the external morphology of the woman's body from the waist down. Obviously, in addition to this there is also the typically female distribution of the subcutaneous fatty tissue on the hips, buttocks and upper parts of the thighs.

Another greatly significant anatomical feature is that, through the genitals, the woman's belly becomes, in a way, "opened" to the exterior. ( Remember that the Fallopian tubes' terminal orifices open directly into the peritoneal cavity. There is nothing similar in the male genitals. )

The vagina can be seen as the canal or "tunnel" that leads to the uterus and the interior of the female pelvis. This means that from the sexual, symbolical and archetypal points of view, it is the "way in" ( and the "way out" ) of the woman's body. The vagina possesses a thin muscular layer and is coated by a mucosa lined by a stratified squamous epithelium highly sensitive to the action of the ovarian hormones. In repose conditions the vaginal walls remain collapsed, but a typical reaction of vaginal lengthening and widening takes place during sexual excitement, culminating with the "ballooning" of the upper third of this organ. The contractile capacity of the vaginal musculature is very small, and the strong contractions that take place around the lower third of the vagina during orgasm do not originate in its muscles but in the muscular groups of the perineum and pelvic floor that surround the vaginal entrance.

The vulva, in turn, is the "doorway" of the vagina. At the genital level, the main areas for women's sexual stimulation are found at the vaginal entrance, the vulvar cleft, the labia minora and majora and, over and above all, at the clitoris ( and, in many women, also at the Gräfenberg Spot ). Behind and around the vulvar structures there are the already mentioned muscles of the perineum and the pelvic floor. They surround the vaginal entrance and are capable of giving rise to strong contractions. During orgasm, they contract rhythmically. Among those that constitute the pelvic floor, the most important one is the pubococcygeus. In cases of vaginismus, the psychologically-triggered strong spastic contraction of these muscles is able to impede sexual intercourse.

Regarding the above mentioned view of the vulva as the female genitals' "doorway," we must observe that, certainly due to powerful archetypal reasons, there are amazing morphologic similarities between several doorways of temples, churches and palaces built by different civilizations of the past and the vulvar structures.

Just like all the other woman's sexual organs, the trophicity not only of the vagina but also of the vulvar mucosa and labia is maintained by the estrogens.

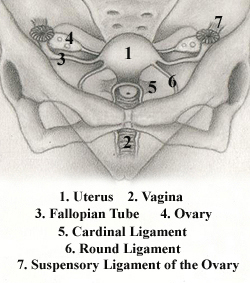

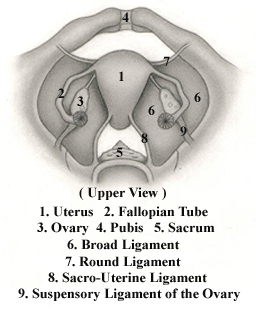

While the uterus

occupies a basically central position inside the female pelvis, the Fallopian

tubes and ovaries are placed bilaterally ( see Note

1 below ). Though entirely explainable for reasons of physiological

order ( in Medicine we use to say that the function determines the shape

), this highly "centralized" uterine position inside the pelvis

also seems to be endowed with a particular symbolism. By the way, there

are very beautiful, perfect, curious and mysterious symmetrical patterns

in the woman's sexual organs, including the equally symmetrical topographic

relations between these organs and the other parts of the female pelvis.

As to that subject of symmetry and its meaning, see Note

2 below.

In spite of the great mobility of the uterine corpus ( the main part of

the womb ), the uterus as a whole remains "anchored" in its

basic position by means of the uterine cervix and an intricate group of

ligaments named retinaculum uteri. These ligaments originate in

the uterine cervix and attach to specific points of the pelvic walls.

Of these, the most important ones are the cardinal and the sacro-uterine

ligaments. There are also the pubo-vesico-uterine ones, but these are

not so important as the former.

The cardinal ligaments are bands of fibrous tissue that extend from the lateral parts of the uterine cervix towards the lateral pelvic walls. The sacro-uterine ligaments are fibro-muscular cords that, emerging from the posterior part of the uterine cervix, attach to the walls of the sacrum. The "anchorage" of the uterus in the pelvis is completed by the round and the broad ligaments, that arise from the uterine corpus and are less tense than the others, which provides this part of the organ with its usual great mobility. The broad ligaments are formed by folds of the pelvic peritoneum that encase the corporal part of the uterus; they emerge from the lateral sides of this organ and attach to the pelvic walls. The broad ligaments give the uterine corpus a curious "winged-like" appearance. The round ligaments are fibro-muscular cords that arise from both uterine upper-lateral angles and run to the inguinal canals, terminating inside the vulvar labia majora.

|

|

The ovaries are linked to the uterus by means of the utero-ovarian ligaments and to the pelvic lateral walls through the suspensory-ligaments of the ovaries or infundibulo-pelvic ligaments; they are also attached to the broad ligaments through the meso-ovaries. The Fallopian tubes, in turn, are "anchored" to the broad ligaments through peritoneal folds named mesosalpinxes.

By means of this intricate and complex ligamentary system, a direct anatomic connection between the woman's inner genitals and her pelvic frame is established. Considering that the morphology of the female pelvic bones all by itself exhibits typical sexual features, the concept of "pelvis" in women must be regarded as a wholeness.

It comprehends

everything that, in this part of the body, characterizes the female sex

: vulva, vagina, uterus, Fallopian tubes, ovaries and respective sustaining

structures, pelvic bones and, finally, muscles of the pelvic floor and

perineum. With the addition of its very typical cutaneous, subcutaneous,

fatty and muscular coating on the hips, belly and buttocks, the external

morphology of the female pelvis only by itself is an important element

of sexual attraction, acquiring great importance in the woman's corporal

image.

Note

1: For more specific details on the uterus, Fallopian tubes

and ovaries, see several other articles of my authorship available here,

in this site, and also at the Museum

of Menstruation and Women's Health.

Note 2: A special meaning was always attributed to symmetry, mostly in the western cultural tradition. From the metaphysical point of view, it seems to reflect some of the fundamental principles and laws of nature. Fritjof Capra observes that symmetry ". . . played an important role in Greek science, philosophy and art, where it was identified with beauty, harmony and perfection." Although observing that in the eastern philosophies the concept of symmetry does not seem to be so important as in the west, Capra remarks that ". . .the mystical traditions in the Far East frequently use symmetric patterns as symbols or as meditation devices. . ." ( Capra, F. - "The Tao of Physics" - Flamingo, London, 1983. )

Note

3: The text above consists of excerpts from the introduction

of the second chapter of my book "Os Órgãos

Sexuais Femininos: Forma, Função, Símbolo e Arquétipo"

("The Female Sexual Organs: Shape, Function, Symbol and Archetype"),

published by Imago Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 1993.

![]()

Nelson Soucasaux

is a gynecologist dedicated to Clinical, Preventive and Psychosomatic

Gynecology. Graduated in 1974 by Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade

Federal do Rio de Janeiro, he is the author of several articles published

in medical journals and of the books "Novas

Perspectivas em Ginecologia" ("New Perspectives in Gynecology")

and "Os Órgãos Sexuais Femininos:

Forma, Função, Símbolo e Arquétipo" ("The

Female Sexual Organs: Shape, Function, Symbol and Archetype"),

published by Imago Editora, Rio de Janeiro, 1990, 1993.

![]()

![]()

[ Home

] [ Consultório (Medical Office)

] [ Obras Publicadas (Published Works)

]

[ Novas Perspectivas em Ginecologia (New Perspectives

in Gynecology) ]

[ Os

Órgãos Sexuais Femininos (The Female Sexual Organs)

]

[ Temas

Polêmicos (Polemical Subjects) ] [ Tópicos

Diversos (Other Topics) (Part 1) ]

[ Tópicos

Diversos (Other Topics) (Part 2) ] [ Tópicos

Diversos (Other Topics) (Part 3) ]

[ Tópicos

Diversos (Other Topics) (Part 4) ] [ Tópicos

Diversos (Other Topics) (Part 5) ]

[ Ilustrações (Illustrations)

]

![]()